Learn how a new Federal Circuit case can teach you how to broaden your design patent filings.

Evidence-Based Claim Construction

Patent Claims with "And/Or"

Drawing Objections

Remember Microfische?

GM Wins Reversal in TC 3747

"So I just re-opened"

ZUP Loses Wakeboard Patent Claims

Illegal Restrictions, Contuinued

Our previous post on the improper USPTO practice of presenting new restrictions for the first time in a final rejection has received an unprecedented response. Thank you to everyone who has reached out and offered support, resources, anecdotes, etc.

As a follow-on, our friends at bigpatentdata.com have provided even further insight into the statistics of this practice. Using their interface (which is awesome, by the way), we were able to search a sample of several thousand publically available cases at the USPTO and immediately pinpoint examples where the USPTO set forth a new restriction, for the first time, in a final rejection. Their data, which is still in the process of being expanded to the full set of public applications, shows that about 1% of applicants are subject to this illegal practice.

Now one might argue that if only 1% of the cases experience this issue, then it is not a big deal. But remember that maybe only 1% of patents are ever litigated. And maybe only 1% of issued patents are ever challenged in an IPR. That does not mean that the issue of a patent being litigated or being subject to IPR is not a big deal. Further, the fact that illegal actions are taken in only 1% of applications does not somehow make those illegal actions any less important.

So let's review an example to illustrate the issue. US 13/519,400 relates to a control system for a surgical navigation system using gesture control. After several rounds of prosecution, the applicant amended the claims further to add some specific limitations related to also including a gesture support attached to the user. Note that the gesture support was in addition to the gesture detection.

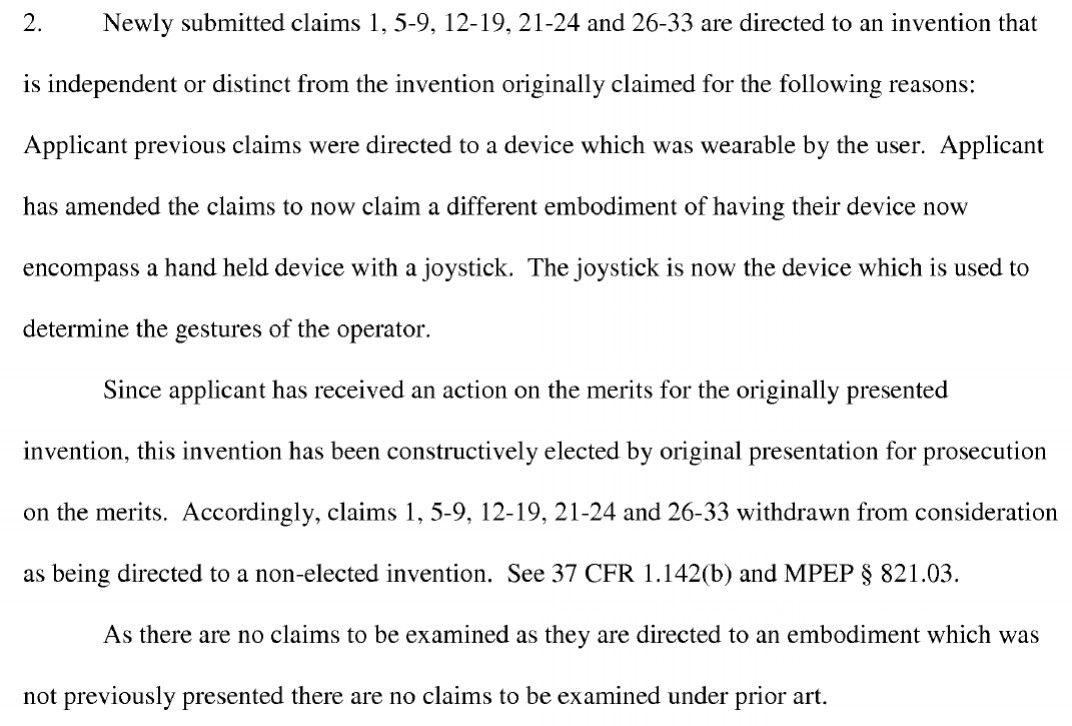

The examiner responded by issuing a final rejection and withdrawing all of the claims as directed to a non-elected embodiment:

So what can the applicant do? They cannot appeal as there are no examined claims or rejections to appeal. They can petition, but there is no guarantee that the Office will issue a decision on the petition quickly. Often such petitions linger for months and then are issued after the six month statutory period for a response as "moot" because the application is abandoned (more on this in another post), so that is not a great option. Therefore, in the end, the only real choice is to pay the RCE fee. And that is exactly what happened in US 13/519,400.

While the Applicant was eventually successful in convincing the Examiner to consider the claims (with still further amendments), they needlessly were required to pay for an RCE (and experience more delay) than if the examiner had followed 37 CFR 1.142(a), second sentence and not issued a new restriction for the first time in a final rejection.